“A Lifelong Journey To Protect Tomorrow’s Inheritance”

Keynote Address

By

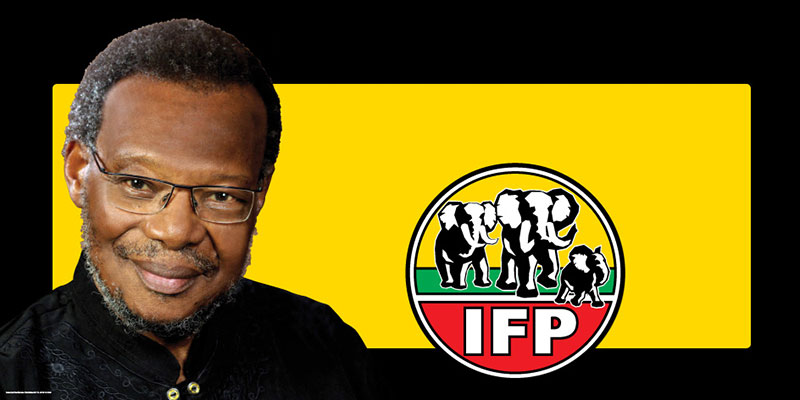

Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi MP

President Of The Inkatha Freedom Party

Mr Nicky and Mrs Orcillia Oppenheimer; Mrs Jennifer Oppenheimer; Mr Phillip Barton, CEO of De Beers Consolidated Mines; Dr Duncan MacFadyen, Manager of Research and Conservation for E Oppenheimer and Son; and all our distinguished researchers and academics.

What a privilege it is for me to be here this morning to listen to the ground-breaking research being done in the field of conservation. When my friend, the late Dr Ian Player, addressed this conference in 2012, he advocated fighting rhino poaching by reopening the sale of rhino horn accumulated through natural deaths. After a lifetime in conservation, having done more to save the rhino than any South African, Dr Player was again rocking the boat.

I understood why he did it. I too have been a conservationist all my life, but still I am not content to leave this fight for the next generation. So long as there is breath in my lungs, I will fight for their inheritance. It may mean trying a new approach, or returning to what worked in the past. But conservation is not a passive pursuit. It demands critical thinking and creativity. It takes innovation and guts. I know, therefore, that the people in this room are our nation’s diamonds. You are bright, tough and have a long-term outlook.

There are two parts to my remarks today. In keeping with the purpose of this conference, I will be speaking about my lifelong passion to protect our natural heritage. But in keeping with the dictates of my own heart, I will also speak about my friendship with the Oppenheimer family. I have always felt the debt of gratitude that is owed to the Oppenheimers. If I am only able to pay it in words, then that is what I will do.

The Oppenheimer family has contributed enormously to the success of South Africa and the economic performance of our continent. One cannot overstate the contribution they have made to improving lives on both a grand and an individual scale. Through their generosity and magnanimity of spirit, underprivileged youth have been educated, the sick have access to health facilities, and communities have gained a sense of dignity. Because of the Oppenheimers, many families have enjoyed an income and our nation has grown its wealth.

I feel tremendously blessed to have enjoyed a personal friendship with Mr Harry Oppenheimer and his wife Bridget, and to continue that friendship with their son Nicky, his wife Strilli, and their children. I must thank the family not only for what they have done, but for what they are still doing for our country. In terms of conservation, they are bestowing a priceless gift that will outlive us all.

My interest in conservation began many years ago. Shortly after my installation as Inkosi of the Buthelezi Clan, in 1953, I was visited by some young rangers of what was then known as the Natal Parks Board. Prominent among them were Ian Player, Nick Steele and Hugh Dent. Somehow, as we discussed our country’s fauna and flora and the challenges to their survival, a deep friendship formed.

At that time there was great controversy about setting aside land for animal reserves. I remember in particular the so-called corridor between the Hluhluwe Game Reserve and Imfolozi. As a result of land dispossession, black people were squeezed into only 13 percent of the land surface of South Africa. So there was a very serious conflict between amaKhosi and their people on the one hand, and the Natal Parks Board on the other.

It was then that Ian Player and Nick Steele approached me, asking that I address amaKhosi from Hlabisa and Mtubatuba about the recently proclaimed corridor, in my capacity as Undunankulu kaZulu: traditional Prime Minister to the Zulu Monarch and Nation. I did so, and that burning issue was extinguished.

But my own interest in conservation had been kindled. I was inspired by the discovery that my forebears, King Shaka and my maternal great grandfather King Cetshwayo, had game reserves. These were not fenced in reserves. But there were rules about hunting in Zulu society. Hunting was only allowed in winter and animals which still suckled their lambs could not be slaughtered.

The needs of conservation had clearly impressed my forebears. In colonial times, and even to this day, were it not for the Zulu game scouts protecting the game reserves, nothing would have survived the commercial poachers.

Unfortunately, conservation had not yet become fashionable by the fifties and sixties, even amongst whites. I remember my friend Nick Steele telling me of an incident in Hluhluwe Hotel where a drunk white farmer was threatening to cut off the pips on his Parks Board uniform, derogatorily calling the Parks Board the “Varke Raad”. Nick Steele challenged him to dare cut it off. That was the extent of the hostility then that existed towards conservation of animals, even amongst whites.

I remember one magistrate talking to me about Dr Ian Player in very derogatory terms, describing Dr Player as “arrogant” merely because he was carrying out his duty to promote the protection of animals. Much later, I remember reading how Dr Player described that time. He said, “Back in the 1960s, game was seen as vermin. Any wild animal which poked its nose outside our reserves would be shot on sight because there was a huge hatred of wildlife and a fear of disease.”

These anecdotes are important to illustrate the kind of hostility to conservation that then existed on both sides of the colour line. African people saw the setting aside of land for animals as meaning that animals were more important than themselves, who were so land hungry, living as they did in crowded so-called “native reserves”.

Ironically, game reserves at that time were playgrounds for whites only. I was the first black to sleep and stay at Mtwazi Lodge in Hluhluwe. Even then there were some unpleasant consequences. The African help who served me there would tell me on my next visit that as soon as I and my family left, they were told to fumigate the blankets we had used during our stay.

On a few occasions I visited Hluhluwe and Imfolozi Game Reserves with my family. If there is anything I regret in life, it is the fact that I have not spent more time unwinding and resting in South Africa’s game reserves. There is no better place to do that.

When I became Chief Minister of KwaZulu in the seventies, some game reserves fell under the KwaZulu Territory, such as Ndumo. I was thus able to establish a Bureau of Natural Resources, in 1982, which later became South Africa’s first Department of Nature Conservation.

For years I was persecuted by the National Party Government which tried to force me to take the great game reserves of Zululand, Hluhluwe/Mfolozi, Ndumo and others, and turn them into agricultural holdings. I said then, and I still maintain, that the game reserves of KwaZulu Natal are our heritage and as such are beyond price.

Mr Ed Gregory headed up the Bureau of Natural Resources and I was able to get my friend, Nick Steele, to take charge of all our game reserves. It was with him that we established the Tembe Elephant Reserve on the border between Mozambique and KwaZulu Natal.

Before he left the Natal Parks Board, Mr Steele had been discouraged by the Board from his friendship with me. I remember being invited to the World Wilderness Congress in San Antonio, Texas, and asking the Board to release Mr Steele so that he might accompany me. But they refused him permission, stating that I was “too controversial” a figure. They could not allow their employee to accompany me.

Fortunately Dr Ian Player had been invited to the conference in his own right, by our mutual friend Mr Harry Tennison, who organized the conference. So I didn’t feel so lonely. Ian’s wife, Ann, accompanied my wife and I.

Ian and I had already worked closely for years, for we shared the fight to build up the rhino population and ensure its survival. By the seventies, fewer than 500 White Rhino remained, but our efforts grew their number in Mfolozi Game Reserve. Dr Player then initiated Operation White Rhino, whereby surplus rhino were captured at Mfolozi Game Reserve and sent to the Kruger National Park and the great zoological gardens throughout the world.

A decade after our first trip together, to San Antonio, Dr Player and Dr Adrian Gardiner accompanied me to Frankfurt, Germany, where I received the Bruno-H-Schubert Stiftung Environmental Award as Patron of the Magqubu Ntombela Foundation.

Magqubu Ntombela had worked with Dr Player in the Wilderness Leadership School which Dr Player founded and of which I am a Trustee. Magqubu could not read or write, but he had an in-depth knowledge of the veld. The mutual respect between him and Dr Player was unmistakable. I think Dr Player judged people according to their heart for conservation, not on their skin colour, education or background.

As an aside, I must tell you that the rhino is a respected animal in Zulu society. I am proud that “Ubhejane”, The Rhino, was added as an extra line in my traditional praises. This came about because of a confrontation I had with the then Minister of Native Affairs, Dr Hendrik Verwoerd. Dr Verwoerd was addressing King Cyprian Bhekuzulu and amaKhosi during a council meeting at Mona Salesyard in 1955, when I was elected to speak. I was just 27 years old, but my contribution must have had an impact because some of my uncles immediately started calling me “Ubhejane”.

That was my first confrontation with a Minister of the old regime, but it would certainly not be my last. I remember being summoned to Pretoria by the Minister of Police Mr Jimmy Kruger, in the seventies, who tried to intimidate me into limiting Inkatha to Zulus. I was perhaps the only black man in a position to stand up to Minister Kruger at that time. It was difficult to come face to face with his particular intransigence.

So imagine my surprise when I discovered that Mrs Bridget Oppenheimer had visited Minister Kruger in the seventies as well, and that she’d given him a piece of her mind. She was always a straight-talker. But my admiration for her was bolstered by the knowledge that she would take on the regime.

In the seventies, at a time when Apartheid did its utmost to keep the races separate, the Oppenheimers and I developed a deep friendship. They would often invite my wife and I to dinner. After dinner, the women would retire to one corner of the room and the men to another where, over cigars, we would inevitably talk politics.

Mr Oppenheimer was a liberal and our friendship enabled me to speak freely. At times so much so that he would have to remind me that President John Vorster could not go ahead of his people. He had to take his people with him.

But I could speak freely with Mr Harry Oppenheimer, and he often responded by asking what business could do to help. At the time, I served as Chancellor of the University of Zululand. Whenever I capped young graduates, I was pained by their honest question: what use is a degree, when there are no jobs to be had?

The economic situation in our country was deteriorating as the campaign of economic sanctions and disinvestment from South Africa really started to bite. Jobs were becoming few and far between as the ANC’s mission-in-exile convinced investors to pull out of South Africa. Industries closed shop and jobs were lost.

I opposed the campaign of disinvestment, witnessing how it affected the poorest of our people the most, and I was vilified for going against the will of the ANC’s mission-in-exile. But, looking back, I have no regrets that I managed to keep some companies in our country and I thank God that I managed to persuade Prime Minister Thatcher and President Reagan not to support economic sanctions.

Saving our economy, saved jobs. But I felt I had to do more. Thus when Mr Oppenheimer asked me what business could do to support genuine liberation, I presented the idea of a technikon that could equip oppressed young South Africans with vocational skills. I wanted to see young people able to take up jobs and create jobs, becoming entrepreneurs and giving their contribution to our society and our liberation.

Mr Oppenheimer immediately grasped the vision. He wanted to be part of a real liberation of our country and sought ways to shape South Africa into a more just, gentle and prosperous society. As the Chairman of Anglo American and de Beers, Mr Oppenheimer had created the Chairman’s Fund. This was not just a showcase corporate social responsibility programme. It met tremendous social needs in our country. Now he would use the Fund to build the Mangosuthu Technikon. With a donation of R5 million, we saw the birth of what is now the Mangosuthu University of Technology.

Mr Oppenheimer also helped fund many training institutes for teachers and nurses. Education was close to his heart. This too made us kindred spirits, for I was fighting a campaign launched by the liberation movement’s leaders-in-exile that called on our youth to abandon their education and burn down their schools.

Across South Africa the cry “Liberation Now, Education Later” echoed through empty classrooms. But Inkatha responded with the clarion call, “Education for Liberation”. We wanted to see young black South Africans equipped with the tools of knowledge, to leverage their own freedom. By keeping schools open in KwaZulu and emphasising the value of education, we prepared young black South Africans to become active, responsible citizens, economic drivers and leaders in a liberated country.

Knowing that education was our shared passion, I took great pride in being capped by Mr Oppenheimer when I received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Cape Town in 1978.

But this was not the only value that we shared. We also stood together against the call for international sanctions and disinvestment from South Africa. This campaign was launched by the ANC’s mission-in-exile with the intention of isolating apartheid South Africa and thus applying pressure towards political change.

I could not support this campaign. I understood that the heaviest burden would be carried by the poorest of the poor, with job losses and deepening poverty. Mr Oppenheimer too could not agree. In an interview in 1987 he said, ”I’m not one of the people who think that sanctions have no effect. I think they have a very serious effect in South Africa, but I think the effect is bad… And it certainly doesn’t force the government to change their policy. You know these highly nationalistic people in South Africa are extremely allergic to pressure from outside. In fact they become very bloody-minded about this sort of thing…”

My opposition to sanctions saw me branded a “collaborator” and a “puppet of the apartheid regime”. From exile, the ANC launched a vicious campaign of vilification against me. It was hard to bear, for I had grown up in the ANC and worked closely with leaders like Inkosi Albert Luthuli, Mr Oliver Tambo and Mr Walter Sisulu. At the request of the ANC leadership, I was working to undermine the apartheid system from within.

But knowing that I was not completely alone fortified my strength to stick to my convictions. Mr Oppenheimer’s shared opposition to sanctions encouraged me to travel throughout the world to reason with Heads of State.

Another instance where he and I stood alone against the consensus was with the introduction of the tricameral system. Through the Homelands system, black South Africans had already been fobbed off and made foreigners in our own country. I rejected nominal independence for KwaZulu specifically to protect black citizenship. With the tricameral system, blacks were again being provoked and told to wait their turn indefinitely while coloured and Indians gained representation in Parliament.

The entire business community and white media hailed the tricameral system as “a first step in the right direction”. I will never forget, for as long as I live, Mr Oppenheimer’s support when I stood against it. He alone stood with me, campaigning for a No vote in the whites-only referendum on 2 November 1983. I was isolated and labelled “irrational”. But I knew that Mr Oppenheimer and I were standing on the side of right.

I found his humility quite remarkable. He spoke so modestly of his contribution to our country’s political freedom, when his contribution was in fact profoundly influential. His own summary was simply this: ”I feel that in the direct political way I was able to achieve virtually nothing, except to keep what I considered a voice of common sense and humanity alive.”

Like his father, Ernest Oppenheimer, Harry had engaged in politics. Ernest Oppenheimer spent 14 years in municipal government, and served as Mayor of Kimberly, before entering Parliament in 1924. Twenty four years later, his son followed him into Parliament.

HFO’s interest in politics endured. When Mandela was released in February 1990, HFO became a mediator trying to arrange a meeting between Mandela and I. We both wanted to meet immediately, but some leaders in the ANC kept Mandela from doing so for a full year.

When we opened constitutional negotiations, HFO stood with me in advocating federalism, when no one else seemed to be interested in the form of state of a democratic South Africa. All that seemed to matter was the transfer of power. When the IFP withdrew from negotiations, it was HFO who flew me to Pretoria to sign a Solemn Agreement on International Mediation with Mr Mandela and President de Klerk.

The full extent of what the Oppenheimers have done behind the scenes, with the utmost integrity and in the interests of our country, will probably never be known. The part of their legacy that everyone will remember is undoubtedly their contribution to the making of a modern economy. Ernest Oppenheimer founded Anglo American in 1917 and gained control of De Beers in the twenties. With the Great Depression in the 1930s, Harry Oppenheimer’s great talent came to the fore. He drove the marketing campaign that coined the slogan, “A diamond is forever”. Thus De Beers and diamonds survived the Depression.

Over the next few decades, the Oppenheimers expanded Anglo American and De Beers, and from the seventies onwards they began diversifying into property, financial services, iron, steel and vanadium, as well as paper. Their investment in our economy has been enormous.

As I have said though, aside from being philanthropists, HFO and Bridget Oppenheimer were wonderful friends. I admired the way they raised their children, teaching them to engage with society and to wisely use their resources to benefit others. When Mr Nicky Oppenheimer retired from the Board of Anglo American, many publications sought to interview him on his illustrious career. The question often arose on what he considered his greatest achievement, to which he answered, quite honestly, “choosing the right parents”.

Having known his parents for so many years, I can understand what Nicky meant. He did not achieve such heights in his career because his parents were rich. He succeeded because his parents fervently believed in investing in education and supporting social development. They were great patriots and they laid a foundation for their children that allowed them to apply their own strengths towards outstanding achievements.

I have great admiration for Mr Nicky Oppenheimer. I will never forget that under his leadership Anglo and De Beers chose to extend antiretroviral treatment to employees stricken with HIV/Aids. National Government had refused to roll out antiretrovirals, saying that it couldn’t be done. It was only when the IFP proved it was possible, by doing so across KwaZulu Natal, that the Constitutional Court was able to instruct national Government to follow suit. I am proud to have shared that fight with Nicky Oppenheimer.

Nicky and Strilli have shown great generosity towards our country, towards strengthening democracy, and towards me. I recall that when the conservationist Sir David Rattray was taken from us, Nicky Oppenheimer flew me to London to speak at the memorial service in Southwark Cathedral. That is just one instance of his generosity, and there have been many.

Over the years, our two families have shared the joy of milestone birthday celebrations, and the pain of funerals. I treasure the road we have walked together.

Friends, I mentioned earlier the significance of the rhino in Zulu culture. I must also mention the importance of the elephant and the lion, both of which I have fought to protect. In his praises, the Zulu King is called “Ingonyama” (lion) and “Indlovu” (elephant), while the King’s mother is “Ndlovukazi” (she-elephant).

Let me speak briefly about our fight for elephants. Between 1980 and 1989, the population of free ranging elephants in Africa dropped from 1,2 million to just 600 000. We needed to act immediately to protect the remaining herds. I therefore set aside 29 000 hectares of land for the Tembe Elephant Park. Other animals, including the Big Five and the endangered Suni antelope, found refuge in the Park from both landmines and poachers.

A few years later, in 1986, I was elected President of the Rhino and Elephant Foundation which was launched at the Everard Read Gallery in Johannesburg. The fact that a group of white environmentalists had chosen a Zulu traditional leader to head the Foundation was significant. It spoke of the link between conservation and reconciliation.

I had high hopes for the Rhino and Elephant Foundation, for it sought a new approach to conservation. As I said at the inauguration in 1986, “The old Africa is vanishing; indeed, much has already disappeared. If rhino and elephant are to be spared the same fate, then far-sighted constructive action must be taken now…. Conservationists all over the world are acknowledging that conventional conservation strategies have failed. The establishment and protection of relatively small areas of wilderness in which creatures of the wild are protected against the ravages of man, while ignoring the realities of the situation outside these ‘green islands’, will not help save the rhino and elephant or any other of nature’s creatures.”

The launch of the Rhino and Elephant Foundation was also the real launch of conservation by consensus. It was here that we began to understand that conservation had to be done with the support and active participation of local communities, and had to be linked to human upliftment. Today this is conventional wisdom, but at the time we were changing the game. It is therefore tragic that the Rhino and Elephant Foundation crumbled under a lack of financial support, and is now defunct.

I am equally passionate about the fight for our lions. Last month, together with Four Paws International, I delivered 545,130 petitions to the Minister of Environmental Affairs, signed by people across the globe who stand in solidarity against the captive breeding of lions for commercial purposes. As Patron of the Wildlands Conservation Trust, I am grateful that the fight against canned lion hunting is becoming more visible, particularly through the recent film “Blood Lions”.

The Oppenheimer family has shared my commitment to wildlife conservation and eco-tourism. Indeed, their commitment has been remarkable. When they bought the Tswalu Desert Reserve in 1998, they ensured the future of a precious part of the southern Kalahari where the rare desert black rhinoceros found refuge, as well as the roan and sable antelope. It is not surprising that conservation initiatives became a characteristic of De Beers, so that today properties within the De Beers Group of Companies and E Oppenheimer & Son are centres of environmental research.

My long journey in conservation has brought me great friends, including Sir Laurens van der Post, Mr John Aspinall, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Sir David Rattray, Dr Ian Player, Mr Lawrence Anthony and Mr Nick Steele. I found another kindred spirit in Harry Oppenheimer.

Today, his legacy continues. As we listen to the research outcomes at the Oppenheimer De Beers Conference, we cannot help but remember the family that set things in motion. Throughout my lifelong journey to protect tomorrow’s inheritance, I have valued my friendship with the Oppenheimer family.

I thank them, and I thank you.